- There are a lot of battery and charger companies out there making claims. Nyobolt is one of them. Its claim is zero to 100% charging of EV batteries in six minutes.

- Is it real? Well, they make a good case. And at the very least they have a nice-looking concept.

- If it’s real, then look for 155 to 200 miles of range from this car’s 35-kWh battery.

The problem with battery chemistry and physics is that not everyone understands them. Once the “experts” start yammering away about anodes and cathodes and ions and electrons, many of us revert to our slack-jawed cave man ancestors so perfectly depicted in Far Side cartoons, staring in awe at what may or may not be the future.

The folks at UK-based battery charging specialists Nyobolt could just as easily be selling time shares and we’d probably buy one. They say Nyobolt’s battery can recharge from zero state of charge to 100% in six minutes just by altering the lattices through which the ions flow, or something like that, and we buy in, hoping that Tampa Beach condo is as nice as it looks in the brochures.

But Nyobolt isn’t the only one making amazing—or possibly absurd—claims about battery charging. Google “Fastest-charging battery” and you get pages of companies claiming they are the fastest. A study discussed in the thoroughly legit IEEE Spectrum says batteries can recharge much of their range in just 10 minutes with the addition of a thin sheet of nickel inside them.

A company called Amprius says it’ll get to 80% in less than six minutes. Enevate’s ZFC-Energy Technology says they’ll do it in five minutes. Prieto Battery Inc. claims three minutes. And we just keep buying time shares in Tampa. “But look at the pool!” we tell the outraged spouse.

Should we believe Nyobolt just because they hired a PR agency that found our email address? I spent about a half-hour talking to two very smart-sounding executives from Nyobolt under their tent in the rain at the UK’s Goodwood Festival of Speed this past weekend.

The company was displaying a Callum-designed Lotus Elise-based electric vehicle with a claimed range of 155 miles in city driving or 200 miles on the highway with the concept’s 35-kWh battery. Nyobolt’s VP of engineering Steve Hutchins said they have charged and discharged their battery at this incredibly fast rate over 2500 times with a total degradation in the battery’s ability to hold electricity of less than 15%.

But how?

“To put a lot of power in, you need to get a lot of current through it. To get a lot of current through, a lot of charge needs to flow in and out of the materials,” Nyobolt co-founder and CEO Sai Shivareddy said. “And the materials need to be engineered to accept a lot of charge transfer per unit time. So that’s basically what the current definition is. The charge transfer can happen if you make the surface more accepting of charge. And that surface is engineered, with materials that we have invented. And also the chemistry itself, to have the demands go in and out like superhighways without any damages because when you’re going in too fast (there are damages), right?”

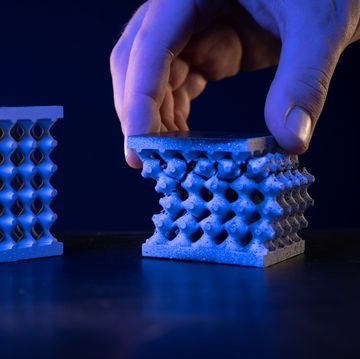

Shivareddy says it comes down to the materials Nyobolt has invented to accept that level of power, without the traditional problem of battery degradation from a lot of fast charging. “So that big problem we’ve solved by not causing the heat that’s normally generated in the first place. The heat’s generated when atoms collide with the lattices inside the particle structure. We’ve engineered these lattices to have superhighways for lithium ions.”

Got that?

But if Nyobolt is such great stuff, why hasn’t anyone else thought this up in the 232 years since Allesandro Volta made his battery in 1791?

“We have been standing on the shoulders of giants,” said Shivareddy. “The lithium-ion battery was invented 30 years ago, and we know that it doesn’t get any better than lithium-ion in terms of energy and power because it’s the smallest and lightest metal you can find on the periodic table. And then once you have the lightest material to play with, we look at all the possible ways to pack a lot of energy in there by storing a lot of charge. That’s what happens when you put them inside the lattices of these materials. Traditionally, the first chemistry that was in the first generation of (modern) batteries, was mostly carbon based. So the carbons have had traditional problems in relation to how much charge can go in at a given time.

“With lithium, if it tends to accumulate on the surface, and the charge transfer doesn’t happen fast enough, the electron coming out to the current can go out, or go in, depending on whether you’re charging and discharging. And then that charge transfer part, it’s limited by two things. One is just the diffusion lens inside the material. So how quickly it can go in a straight line or by colliding with particles. So you have more collisions, you have more heat. So we solve for that, then you can actually get a fast charge in the same time it takes to refuel your traditional car.”

So there you have it. A little short on specifics, a little long on general theory. If you make it easy for the electrons or the ions to go through the lattices, you can charge and discharge at incredibly high rates. This also suggests that as you discharge at a high rate, you could theoretically get a monster 0-60 mph time, for instance.

Is Nyobolt the savior of our electric future? Or do they just have a really nice electric show car? Please comment below.